Circularity strategies

In Quebec, as elsewhere in the world, circular economy is about much more than just recycling. It is a coherent and structuring framework that brings together a set of strategies all contributing to the same objective: meeting society's needs while preserving resources.

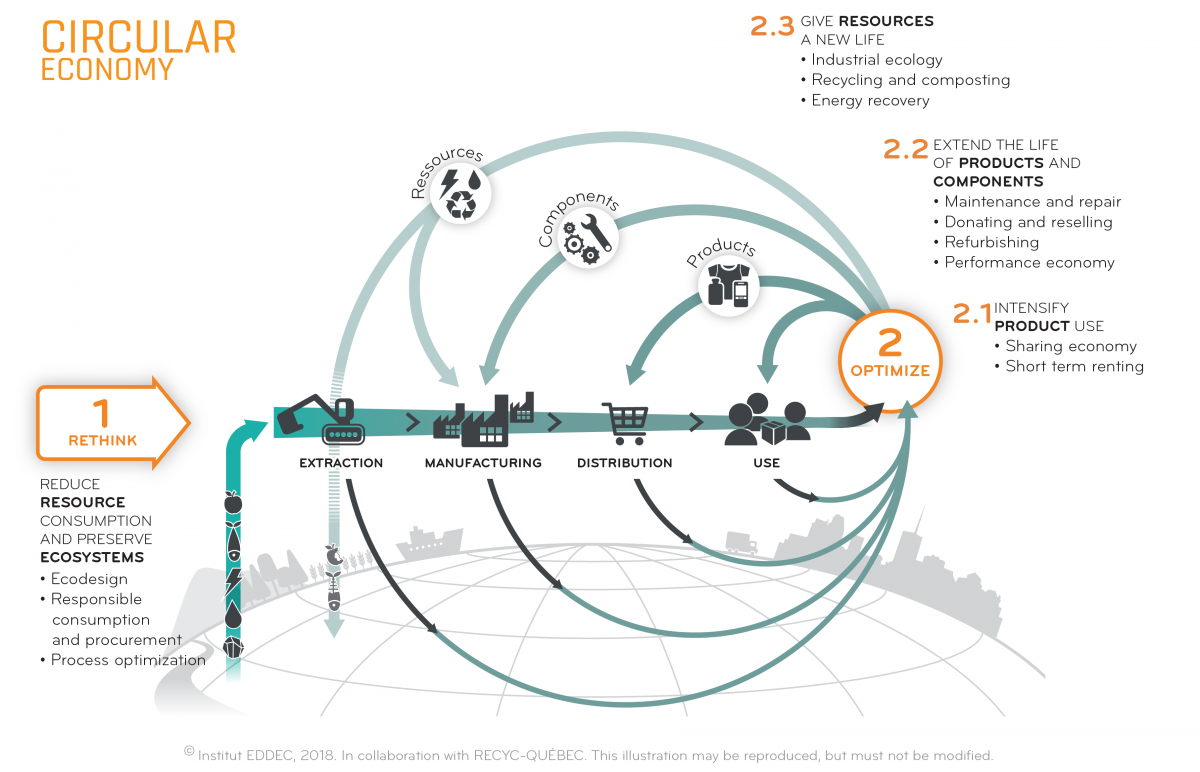

This economic model proposes twelve strategies that organizations and regions can select and adapt according to their context and the type of resources they use. In general, the first priority is to develop strategies that (1) reduce the number of virgin resources consumed. Next come "short loop" strategies that aim to (2.1) increase the use of products and those that aim to (2.2) extend the lifetime of products. Finally, there are strategies that (2.3) give a new life to resources.

Download the diagram in english

** Download the summary document on circular economy for an overview and further details.

- Design products that simultaneously meet several functions.

- Reduce the amount of resources required to manufacture and use a product.

- Favour low-impact resources (those that are renewable, non-toxic, reusable, recycled, etc.).

- Avoid contaminating bio-based components with toxic inputs so that they can simply be returned to the earth after use or recovery.

- Promote prolonged use of the product (it must be durable, repairable, easily updated, etc.).

- Draw inspiration from nature when designing products (biomimicry). There is no such thing as waste in Nature, which benefits from billions of years of evolution. It is an inexhaustible source of inspiration for designers

For more information on eco-design, visit Éco Entreprises Québec, by CRIQ and the Institut de développement de produits

Responsible consumption and procurement initiatives can be enhanced by circular economy model, which proposes new purchasing criteria focused on the optimal use of our resources. Individual and organizational consumers obviously have a key role to play in reducing resource consumption. They are the ones who can question their real needs for acquiring new goods and give preference to products with a low impact on resources and the environment.

At organizational level, the development of new business models, such as functional economy and the sale of used or refurbished products, will encourage some companies to switch to closed-loop logistics. They will be able to source directly from their products at the end of their life cycle or from similar products. This approach gives a better recovery rate and good control over the quality and quantity of material available for the manufacture of new products.

To learn more about these strategies, visit ECPAR and l’Observatoire de la consommation responsable.

The roadmap Industrie 4.0 may be an interesting vehicle for deploying this strategy by taking advantage of new technologies, in particular:

- Information management systems to better manage resource consumption, target losses, and effectively plan distribution logistics.

- Additive manufacturing (including 3D printing) also has interesting potential for saving resources. Studies show that the new technologies it brings together would reduce material consumption in the metals sector by 70%. (in French)

Its development generates new and complex issues (responsibility, quality, safety, taxation, etc.) that require the contribution of different people and disciplines to answer them. In Quebec, the collaborative economy working group (in French) made twelve recommendations aimed at collectively reaping the benefits of the collaborative economy and supporting its transformation in an informed, accountable and transparent manner.

The academic community is also the driving force behind this transition, in particular the Responsible consumption observatory and the CERIEC (Center for Intersectoral Studies and Research on the Circular Economy).

With rental, an organization or individual owns something and rents out its use for a fixed period of time. This strategy is well known in some sectors, such as tooling, the automobile industry and real estate. By making it unnecessary for customers to purchase property that they use only occasionally, rental can help to get the most out of them. This business model therefore meets the same objective as the collaborative economy, but is more suitable for customers who do not want to be in contact with other users of the same property.

With rental, the management of end-of-life products may be less efficient than in functional economy (see strategy 9) where the manufacturer retains ownership and can therefore more easily recover, repair and recondition them and ultimately reinsert them into their production cycle. However, lessors also have a vested interest in ensuring proper maintenance and repair of their assets in order to maximize their return on investment. Under the impetus of circular economy, rental is now expanding into new sectors, such as fashion and textiles.

Today, the cost of repair is often higher than buying a new similar product. This situation is caused by the fact that the environmental and social impacts of the manufacture and distribution of goods are not taken into account in their prices. The attractiveness of new things is also an obstacle to repair and increasingly rapid technological progress means that the products to be repaired are already completely obsolete after only two or three years of use. Fortunately, consumer mentality is changing and several interesting opportunities are now available, including:

- The site iFixit.com, which contains thousands of free repair guides and sells parts online.

- Repair Cafés, which are pop-up repair workshops where people can bring their equipment to be repaired and get help from experts who offer advice and technical support.

Manufacturers must nevertheless take action to design products that are easier to maintain and repair. Fortunately, in Europe, some legislation on product obsolescence is beginning to emerge.

For an overview, watch this short report broadcast on Télé Québec on the program Ça vaut le coup (in French).

Giving away and reselling allow consumers or organizations to put back into circulation products that they no longer need, but which are still in good condition. These strategies are far from recent, but new digital platforms offer unprecedented opportunities to connect those who want to dispose of objects with those who are looking for them.

The Kijiji 2019 Index (in French) points out that:

- the second-hand economy is steadily expanding and generated approximately $27,3 billion in economic activity in Canada in 2018;

- among the most exchanged goods are baby clothing and accessories; games, toys and video games and clothing, shoes and accessories;

- the primary motivation to acquire second-hand goods is the lower cost but ecological and altruistic motivations are growing.

However, giving away and reselling may conflict: if it is now easier to resell their used products, will consumers tend to favour this strategy over giving them away? Fortunately, more and more organizations, often from the social economy, are making it easier to collect gifted goods and, increasingly, online services are making it easier to donate to charities.

Reconditioning involves restoring a product or component to a condition as good as new, with a guarantee equivalent or close to that of a new product. The product is collected, transported and disassembled. Each of its components is cleaned and checked, and some of them are changed or reworked. The product is then reassembled, checked and put back on the market. The possibilities for reconditioning depend greatly on the industrial sectors. In the transport sector, reconditioning is applied mainly to heavy or military equipment with very long life cycles (boats, trains, planes and helicopters), but not so frequently for lighter finished products, such as cars. In the energy, infrastructure, mineral processing and building sectors, energy is produced with equipment whose life cycles extend over decades, a favourite area for reconditioning. A component can also be reconditioned when its service life is shorter than that of the host product: reconditioning is part of a maintenance operation and competes with replacing the product with a new one.

To make this strategy easier to deploy, products must be designed taking into account the requirements of their end-of-life processing. The shift to business models such as the functional economy could change this by encouraging manufacturers to use closed-loop logistics in which they reinsert the components of their second-hand products into their new product manufacturing process.

By retaining ownership of the product, the manufacturer can adequately manage the end-of- cycle stage. The product can then be repaired, reconditioned or dismantled to generate new components or raw materials. The manufacturer is therefore partly freeing itself from the volatility of raw material prices.

According to initial studies, the functional economy could be a win-win situation: manufacturers, consumers and workers would all benefit from this new model, which would also significantly reduce the environmental footprint. Considered as a "disruptive organizational innovation," the functional economy significantly modifies customer-supplier relationships, as well as the design and management of the product life cycle.

Industrial ecology is a multidisciplinary approach, including a set of tools such as eco-design, clean technologies and life cycle assessment. It seeks to optimize the use of natural resources in the industrial processes. Seeking inspiration from natural cycles, where material and energy are constantly recycled, industrial ecology applies the same idea to the value chain and its residual wastes.

More specifically, industrial symbiosis is a network of businesses and collectivities who are exchanging materials, byproducts, water, energy and innovative practices. Industrial symbiosis may be autonomous or facilitated by a third-party agent.

In Quebec, the Synergie Québec network brings together over 20 industrial symbiosis initiatives. This community is led by the Industrial ecology technology transfer Centre (Centre de transfert technologique en écologie industrielle - CTTÉI).

Text written by CTTÉI

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE CIRCULARITY OF MATERIALS

Recycling is the use in a manufacturing process of recovered material to replace virgin material. Circular economy firstly makes it possible to set up the shortest possible recycling loops, thereby favouring local recycling markets over export markets. Secondly, in order to preserve the value of resources, it invites people to focus on recycling in products with high added value (upcycling).

Composting in a circular economy, organic matter returns to the soil to enrich it. In this sense, composting is aerobic (taking place in the presence of oxygen) processing of organic matter, which creates a mature solid product: compost. Compost is a stable product, rich in humus compounds, which is mainly used as a soil-enriching agent.

Text written by Recyc-Québec

Energy recovery may involve heat treatment processes that will irreparably transform materials such as incineration with energy recovery, combustion in an industrial boiler or cement kiln, pyrolysis and gasification. According to the French environment quality act, the thermal destruction of residual materials counts as energy recovery as long as this processing meets the regulatory standards prescribed by the government, including a positive energy balance and the minimum required energy efficiency, and helps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These aspects are important ones to consider from a circular economy standpoint.

Text written by Recyc-Québec